68 People Are Nearly Blind After A Botched Drug Was Injected Into Their Eyeballs

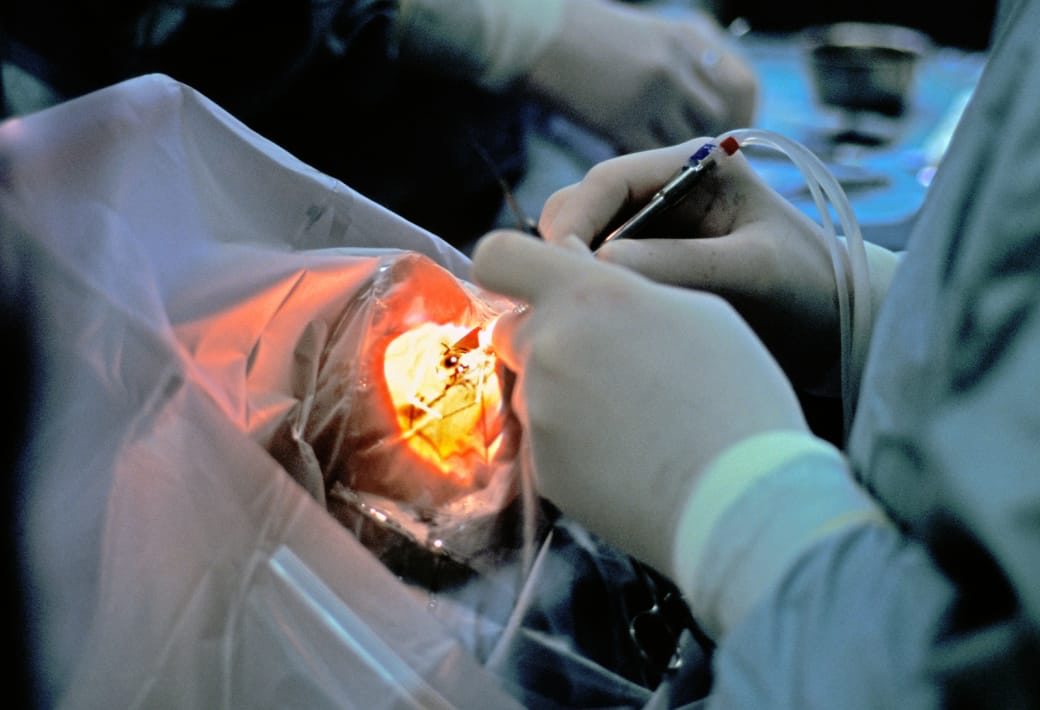

Their tragedies expose a shadowy US industry that sells drugs with little government oversight, in Dallas, Texas Like millions of Americans around retirement age,Curtis Cosby was getting cataract surgery to replace the cloudy lens in his right eye. After the quick procedure, the doctor injected a medication that was supposed to speed up healing and spare him the inconvenience of buying eye drops later. That sounded good to him. He’d been a truck driver since he was a teen and just wanted to get back on the road as soon as possible. One afternoon two weeks later, Cosby was driving a 10-wheeler back from Oklahoma when something blew through the open window and into his left eye. He rubbed it. Only when that eye was covered did he realize that he could not see out of the one that had just been operated on. Frightened, Cosby pulled over. He called his surgeon, Kate Lee — something had gone wrong, he told her — and she invited him to come in the next day. At the appointment, he recalled, she looked him in the eye and apologized.

“What do you mean, ‘I’m sorry’?” he remembers responding. Lee explained that there had been problems with the injected drug, and that other patients had come in with the same symptoms. A retina specialist next door gave Cosby aspirin in the hope that it might increase blood flow to the back of his eye. It didn’t.

He’s one of at least 68 cataract patients in the Dallas area who say they were partially blinded or worse within days or weeks of being injected with a knockoff version of a drug called TriMoxi. Some cannot perceive depth or colors. Others see glare, halos, flashing lights, or darkness. Many are constantly disoriented, plagued with headaches and nausea, unable to drive or work. Now, they’ve lawyered up against the pharmacy that mixed the drug, the company that allegedly designed the shoddy recipe, and the clinics that injected it. Two of the patients filed lawsuits last week, and several dozen others, including Cosby, are lined up to join them. The defendants are pointing fingers at one another. The company accused of coming up with the drug’s recipe, the Professional Compounding Centers of America (PCCA), denies it did so, and says that the trouble was caused in part by the pharmacy that mixed it, Guardian Pharmacy Services. Guardian, meanwhile, says there’s no link between its products and the patients’ vision problems, which were known complications of the surgery. And the clinics that performed the surgery — which typically has a low rate of complications — say the drug was certainly to blame.

The lawsuits spotlight the shadowy, booming industry of “compounding pharmacies,” companies that make drugs for people who need customized products that aren’t sold by pharmaceutical companies — such as a pill in liquid form. Federal law dictates what types of ingredients can be used in compounded drugs, but nobody is required to test whether the end product is safe and effective. Consequently, companies like PCCA and Guardian are free to formulate or sell untested drugs with little government oversight.

In 2013, after mistakes at one such facility in Massachusetts led to 64 deaths, Congress passed a law intended to increase the FDA’s authority. The industry balked, arguing that states were already providing adequate oversight. Critics, meanwhile, faulted the law for being too weak, saying that its loopholes allow the bulk of the industry to continue business as usual. Some of the companies named in the Dallas lawsuits have checkered pasts, a BuzzFeed News review of FDA documents, court filings, and state pharmacy board and business records shows. In 2010, for example, PCCA was sued for allegedly formulating yet another drug that blinded a patient. (The case was settled without an admission of guilt.) And two Guardian executives previously helped run illegally operating internet pharmacies, roles that led to the suspension of their licenses — and for one of them, a felony conviction.

“It’s hard for me to remember a case in which there has been such disregard for patient safety regarding the preparation of a compounded drug,” Larry Sasich, a pharmacist in Ontario, Canada, who tracks the compounding industry and is not involved in the lawsuits

ingredients into remedies, or compounding, dates back to ancient Egypt and Rome. In the US, compounding pharmacists made most medications until the 1960s, when big pharmaceutical companies started mass-producing drugs and overtaking corner drugstores. Compounding never disappeared, though, because it fills legitimate needs. Sometimes a patient is allergic to an ingredient, or wants a medication to have a different flavor, or needs a different dose. The industry began to grow again in the 1980s, spurred in part by PCCA. Formed in 1981, the trade organization aimed to revitalize the practice by supplying chemicals to its member pharmacies, sharing its recipes (or “formulas”) with them, and later promoting compounding in pharmacy schools.

Although compounders aren’t allowed to copy any medication (whether patented or generic) that is readily available, they can make substitutes for drugs that are off the market or in short supply. Unlike Big Pharma, these businesses don’t need to get their drugs approved by the FDA, and they generally don’t make proprietary products. Their business is more like a grocery store, dependent on local demand. But compounding can still be lucrative because the ingredients tend to be cheap and companies don’t have to pay for rigorous safety testing. It’s hard to assess the scope of the industry, but trade groups estimate that today about 7,500 independent pharmacies specialize in compounding in the US, and at least 1% of all prescription drugs nationwide — roughly 40 million prescriptions a year — are compounded. One market research firm estimates that by 2022, the global compounding industry will bring in $12 billion. Sixteen years later, a deadly fungus contaminated drugs made by the New England Compounding Center in Massachusetts. As a congressional investigation would later reveal, things went wrong partly because of confusion over which regulatory body was responsible for keeping the company in check. The state pharmacy board had investigated the compounder a dozen times, and the FDA had inspected three times, before the contaminated drugs sickened nearly 800 customers across 20 states and killed more than 60 of them. The pharmacy’s owner has since been convicted of more than 50 counts of mail fraud and racketeering.

More than 3 million people in the US and some 20 million globally get cataract surgery every year. After the outpatient procedure, patients are typically prescribed antibiotic eye drops to curb inflammation and infection. But most use the drops incorrectly. The Dallas patients are suing over a medication that was sold to them as an alternative to those drops. Although their knockoff TriMoxi was mixed by Guardian, the drug was originally developed by yet another compounder marred in legal controversy. TriMoxi’s history shows not only the big business of cataract surgeries, but the fiercely competitive side of the compounding industry.